Destination-Based Business Cash Flow Taxes

Destination-based business cash-flow taxes have received a great deal of attention and are being widely considered as a replacement for traditional, origin-based, corporate taxes. These taxes combine the strong revenue-raising ability of a VAT with an enormously expensive tax deduction for wages. They would certainly be attractive to foreign investors by eliminating the burden of current corporate taxes. However, adopting them at the rates typically discussed would raise consumer prices dramatically. A more fundamental problem is that practical versions of such taxes would likely reduce net government revenues in countries adopting them.

Destination-based business cash-flow taxes have received an enormous amount of attention in recent years. A proposal to change the US corporate tax system from a traditional corporate income tax to a destination-based one that exempts exports from taxation, and allows deductions only for domestic inputs came close to being adopted in 2017 (Ways and Means Committee 2016). An eminent group of tax experts are currently advocating such a tax for implementation in a wide range of countries, including those currently operating Value Added Taxes (Auerbach, Devereux, Keen and Vella 2017). The Financial Times recently ran an editorial advocating such a change (Financial Times 2018). And CESIFO is holding a conference on this issue in the summer of 2018 (CESIFO 2018).

Advocates for this proposal claim several advantages for this shift from traditional corporate taxes levied on all firm sales, whether sold domestically or on export markets. One problem with traditional taxes is that, in a world of increasingly mobile capital, countries are reducing tax rates and their tax revenues are falling. Many advocates claim that the revenue yield from a destination-based tax would be substantial (Patel and McClelland 2017). Many also claim that the burden on consumers associated with the increase in consumer prices they create would be reduced—or even eliminated—by an appreciation of the exchange rate (Feldstein 2017). This proposal is extremely attractive to foreign investors because it would free them from traditional obligations to pay corporate taxes, and so adoption in even one major country would put pressure on other countries to follow suit.

With such strong advantages, surely policy makers in many countries should be rushing to adopt such measures? Why wait to be forced into responding to the tax policy decisions of other countries? Why not start to reap the benefits in terms of higher revenues? And, given the importance of foreign investment in the development strategies of many low and middle-income countries, why pass up this opportunity to become more attractive to foreign investors?

Some skeptics have, however, raised some concerns. One is whether the foreign exchange appreciation thought to be associated with this proposal might create competitiveness problems (Eichengreen 2017). Others have expressed doubt about whether there would be an appreciation at all. For reasons explained in this paper, I’m very concerned about the likely very small, volatile and likely negative net revenues from such taxes once we recall that much of this revenue is from higher prices that the government must pay for its purchases of goods and services (Martin 2018a,b).

The purpose of this note is to review some of the arguments involved when considering a move to destination-based taxes. The next section considers what they involve. The third section looks at their impacts on prices and wages, while the fourth section looks at real exchange rate effects. The fifth section looks at tax rates and the tax base, while the final section summarizes.

What are Destination-Based Business Cash-Flow Taxes?

Under a destination-based business cash flow tax, firms submit a tax return which requires them to pay tax on domestic sales and allows them to benefit from deductions against use of domestic inputs, including labor. The difference between a destination-base tax and the familiar origin-based tax is that, under the destination approach, no tax is levied on export sales, and no deduction is allowed for imported inputs. This tax is like an origin-based corporate cash-flow tax (Abel et al 1989) or most Value-Added Taxes in allowing immediate tax deductions for capital expenditures, rather than allowing deductions for capital only in line with its depreciation.

A major difference from traditional corporate taxes—and a point of similarity with Value-Added Taxes (VAT)—is that such a destination-based tax must be levied on all business income, rather than merely that from corporations. While many earlier discussions of the destination tax focused on corporations (Auerbach 2010), anymore recent treatments have broadened their coverage to include all businesses (Auerbach et al 2017) and the proposal debated in the United States during 2017 included unincorporated enterprises as well as corporations (Ways and Means Committee 2016, p24).

Impacts on Domestic Prices and Wages

Use of the destination approach has profound impacts on domestic prices. These are perhaps most easily seen in the case of an exportable good. A producer facing the choice of whether to export or sell domestically must consider the difference in the tax treatment of the two sales. If he chooses to export, no tax is liable, and he continues to receive the initial price of, say, $1 per unit. With a 20 percent tax, he needs a domestic price of $1.25 to maintain the $1 net return she could have obtained from the export market. This means that domestic consumer prices of exportables will rise by 25 percent following the imposition of a cash-flow tax at 20 percent, while producer prices will remain at $1. If unincorporated enterprises were not included in the destination-based business tax net, they could undercut corporations by selling at $1 in the domestic market, creating enormous disincentives for firms to use a corporate structure and undermining the increase in domestic consumer prices needed for the tax to raise revenues, just as a VAT does.

A similar effect operates for imported goods. An importer who brings in a good valued at $1 must raise his selling price to $1.25 if he is to cover the costs of a 20 percent cash flow tax. A corporate purchase buying the good as an input would receive a 20 percent tax deduction, lowering its cost to $1, while a final consumer would not receive a tax deduction and so would pay $1.25. This 20 percent tax is equivalent in its effect on prices to a 25 percent VAT imposed using the traditional approach where VAT is collected on imports and exempted on exports at the border.

For a long run change such as a tax reform, it makes sense to focus on longer run changes in prices and wages, and to abstract from short-term considerations of wage stickiness. In this situation, the deduction allowed for labor costs creates a similar gap between the net wage cost to employers and the wages received by workers. Since the prices received by producers for outputs and paid for inputs have not changed, there is no change in the wage rates they can afford to pay. The deductibility of wage costs means that firms facing a tax of 20 percent can, however, afford to pay $1.25 for labor that previously cost them $1. Workers are now paying 25 percent more for the goods that they buy, but receiving 25 percent more in wages, leaving them just as well of (or poorly off) as before, and with no incentive to change the amount of labor they supply.

The immediate deductibility of capital goods appears to provide an incentive to investors. However, this deduction plays a completely different role in a destination-based tax than under an origin-based tax such as the current corporate income tax. Remember that the effect of the destination-based tax is to raise the prices of goods sold domestically. The deductibility of capital investment is, in this case, just a way of relieving investors from the increase in their costs that would otherwise arise from the tax. No deduction for depreciation costs is required because producer prices, wages and profits are unaffected by the tax.

Real Exchange Rate Impacts

The claim that a destination based corporate tax will cause an exchange rate appreciation appears to be based on a situation in which nominal prices of consumer goods are held constant, perhaps by a tight monetary policy that refuses to allow an increase in consumer prices. In this situation, the only way that consumer prices can rise relative to producer prices—as required by the tax— is for producer prices to fall. For a small country, this requires that the nominal exchange rate appreciates. If, for instance, Morocco introduced a destination-based corporate tax at 20 percent and refused to accommodate the needed 25 percent increase in consumer prices, an appreciation of the Dirham from 0.11 $/Dirham to 0.1375 would bring about the required fall in domestic producer prices.

But this nominal appreciation of the currency has no impact on the relative prices that matter when considering tax policy. It does not matter to producers or workers whether the required change in the prices of consumer and producer goods comes about by a 25 percent increase in consumer prices with producer prices held constant, or a 25 percent decline in producer prices with consumer prices held constant. As shown in Martin (2018a), there is no reason to expect any change in the real exchange rate from introduction of such a tax. The “relief” from the burden of the tax on consumers promised by Auerbach and Holtz-Eakin (2016) is similarly a myth.

The Tax Rates and the Tax Base

The total rate of tax imposed on consumer goods under a destination-based corporate tax depends heavily on whether it is introduced in addition to other consumer taxes such as a VAT. Under the US proposals (House Ways and Means Committee 2016), this tax would have been introduced in the presence of consumer sales taxes that average 6.4 percent and range up to 10 percent. As noted in Martin (2018a), this would have resulted in average total tax rates on consumers of 33 percent, and up to 37 percent in the highest-tax states. This is more than twice the international average VAT rate of 16 percent (EY 2017), and high enough to create substantial incentives for tax evasion and avoidance.

If a destination-based corporate tax were introduced in a country that already has a VAT, this problem of compounding tax rates would be much more serious. Combining a 20 percent destination-based corporate tax with an average VAT of 16 percent results in a combined tax rate on consumer goods of 45 percent1. If it were combined with a high VAT rate, such as the 27 percent applying in Hungary, the combined tax rate on consumer goods would be 59 percent. Such high rates would lead to extraordinary pressure for avoidance and evasion.

One approach to dealing with the incentives for avoidance and evasion would be to abolish existing VAT taxes, whose effect on consumer prices is replicated by destination-based taxes on goods. Because a traditional VAT is generally introduced by levying taxes at the same points as traditional consumer taxes—and particularly at the point of sale for consumer goods—the compounding effect of a VAT and a traditional consumer tax is obvious. As a result, a large part of the challenge in introducing a VAT in a country with existing consumer taxes is the elimination of most other consumer taxes (Shah Doshi 2018). The destination-based corporation tax makes this problem less obvious, but no less serious.

The thought experiment of eliminating the VAT and introducing a destination-based corporate tax at the same rate reveals the fatal problem of this tax proposal for any country with an existing VAT. Since a standard VAT is a tax on private final consumption, elimination of the VAT reduces government revenues by the tax rate times private final consumption. The taxes on goods in the destination-based tax proposal could replace these tax revenues. But the destination-based tax also includes a deduction for wage costs. With a tax at 20 percent, this would require an outlay of 20 percent of the post-tax wage costs (or 25 percent of the pre-tax wages). While the labor share varies between countries and over time, it is typically over 50 percent of GDP, and has been roughly 60 percent of GDP in the United States in recent years and closer to 66 percent in France, Germany and the UK (EC 2018). Replacing a VAT with a destination-based corporate tax in a country with a 65 percent labor share would mean a fall in revenues of 13.2 percent of GDP. This is just below the average rate of total tax collections in the world of 15 percent in 2015, and equal to the average tax collection rate in 2009 (World Bank 2018).

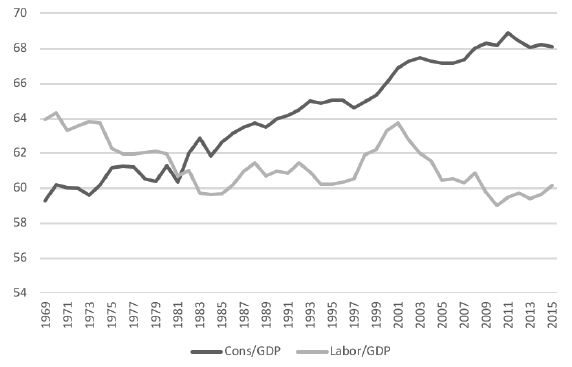

Clearly, few countries could afford such a jaw-dropping reduction in tax revenues. In this situation, countries with a VAT or other sizeable consumer taxes, would need to maintain these taxes and accept the problem of cascading tax rates leading to extraordinarily high tax rates on consumers. Surely, then, such a tax would generate substantial net revenues? In fact, the revenues from such a tax would be small, volatile and vulnerable to turning negative. Figure 1 shows the two key elements of the tax base as shares of GDP for the United States. The black line in this figure is private final consumption, which is the base for revenue collections from this tax. The grey line is wages, which are a tax deduction to firms and, hence, a source of net outlays under this tax proposal. As is clear from the Figure, this tax would have generated negative revenues during the period up to 1982, when the wage share was higher than it has been in recent years, and the consumption share was substantially lower. Since that time, total spending—including private final consumption—has risen relative to income in the United States, resulting in a sharp increase in the current account deficit. At 2015 consumption and wage shares, the tax base for this tax would have been around 8 percent of GDP, resulting in revenue collections of around 2 percent of GDP. But this revenue would shrink and could become negative if consumption spending fell relative to GDP, perhaps out of a need to reduce the current account deficit, or if the share of wages in GDP rose, as it did between 1994 and 2002.

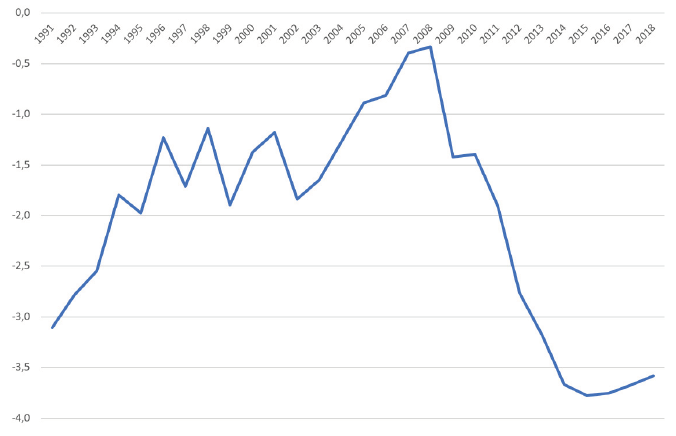

In many other countries, the net revenue outcome would be much worse than in the United States. Had such a tax been imposed in France, for instance, the tax base would have been negative in every year since 1991, as shown in Figure 2. In practice, the net revenue situation in both countries would be even worse than is suggested by the conceptual measures presented in Figures 1 and 2. Some parts of private final consumption, such as the services provided by owner-occupied dwellings, the services provided by nonprofits to the private sector, and many outputs of the financial sector are very difficult to tax under destination-based taxes such as VAT (US Treasury 1984) or the proposed destination-based cash-flow tax. Martin (2018a) shows that net revenues in the United States would have been negative in all years had just the services provided by owner-occupied dwellings and by nonprofits been excluded.

Much confusion on the revenue prospects for a destination-based corporate tax has been created by studies such as Patel and McClelland (2017) that look at the tax returns of individual firms and calculate the taxes they would pay—or the rebates that exporters would receive. While such studies accurately measure the gross revenues that companies would pay, they do not account for the fact that price increases on products sold to government create both an additional revenue and matching additional expense to government, and so do not contribute to net government revenues. Such revenues are no more a contribution to net government revenues than a transfer from my left trouser pocket to my wallet is a source of net cash income to me. In this respect, a destination-based corporate cash flow tax is quite different from the origin-based cash flow tax considered by Abel et al (1989).

Summary/Conclusions

Competitive reductions in corporate taxes and the consequent fall in revenues have raised a great deal of concern amongst governments keen both to raise revenues and attract foreign investment. Destination-based corporate cash-flow taxes have been widely promoted as a solution to these problems, with two key claims: (i) that they can raise ample revenues, and (ii) that they cause an exchange rate appreciation that lowers consumer prices and reduces the burden on consumers. Some also feel that the way they raise prices of imports and lower the prices of exports will lead to increased competitiveness.

It turns out that each of these claims is incorrect. Taking them in reverse order, a destination-based corporate shares a key feature of a VAT in raising the prices of consumer goods relative to producer prices. It does not introduce a trade barrier or increase competitiveness. There is no reason for such a tax to cause a real exchange rate appreciation. The net revenues from such a tax in a country without a VAT would be small, volatile and likely negative. If used to replace an existing VAT, the loss in net revenues would be dramatic. If introduced on top of an existing VAT, the combined tax on consumers would be enormous and the incremental gain to revenues very small. There seems to be no coherent role for such a tax.

Figure 1. The consumption share and the labor share of US GDP, %

Source: Martin (2018a).

Figure 2. The tax base for a destination-based corporate tax, France % of GDP

Source: EC (2018).