The Global Outlook and Morocco

Despite fraught politics, the global outlook is strengthening. The next twelve months are likely to be characterized by moderate but steady growth across the world. However, the outlook becomes murkier as we move into the second half of 2018 and 2019. Significant upside in world economic growth is possible on account of building momentum against a background of low capacity utilization, but even greater downside is possible on account of inconsistent economic policy in the Unites States, Chinese imbalances, and the threat of protectionism. Accordingly, while Morocco’s short term prospects look solid, adjustments are needed to make growth sustainable in the face of likely external turbulence.

The short-term outlook

World GDP growth, measured in real terms at market exchange rates, is likely to accelerate in 2017 to 2.5%-2.7% from 2.2% in 2015. This represents a clear improvement but also indicates that, even against a background of underutilized capital and labor, and 8 years after the great financial crisis, the world economy will struggle to match its 25-year trend growth rate of 3%. As I have argued previously in these pages, policy-makers should adjust to the reality that the long-term sustainable rate of world economic growth has slowed by some 0.5%. The secular slowdown (not stagnation as some have argued) is due mainly to demographics and the exhaustion of the positive shock from the acceleration of globalization which corresponded to the fall of the Berlin Wall more than a quarter of a century ago, and which is most clearly seen in slowing productivity growth.

The evidence that the world economy has gained modest momentum over the last 3 months is most evident in robust PMI indexes. For example, the Markit Global Sector PMI report in April showed every one of 8 sectors covered above the threshold of 50, indicating faster growth, with telecommunications, industrials and financials above 54 and above their first quarter average. Consumer confidence surveys also pointed to strength, especially in the United States, China and Japan, as does the buoyancy of stock markets. Confidence in emerging markets, where stock prices have been especially depressed appeared to return. The improved sentiment is reflected in momentum measures of industrial production and world trade. According to the Netherland Plan Bureau, world trade volumes were up 2.7% in the 3 months to February 2017 over preceding three months, while world industrial production was 0.9% up (chart).

In 2016 Q4 GDP outcomes which came in near long-term estimated growth paths of 1.5%-2% in advanced countries and 7% in China. Flash first quarter 2017 GDP estimates for the US and UK have been below expectations but these numbers are volatile and prone to revision.

The global recovery reflects policies, pent-up demand and the effects of building momentum. Policy interest rates remain near zero in the Eurozone, the UK and Japan, and are expected to rise only gradually in the US over the next year, by about 100 basis points, remaining well below the long-term average. Fiscal policy is expected to add ½% to 1% to aggregate demand in the United States in 2018, and China’s fiscal and credit stimulus – which helped stabilize the economy in 2016- is expected to persist as needed. Fiscal policy will add very modestly to aggregate demand in the EU. The divergent monetary and fiscal policies in the US and the EU will likely imply continuation of a high dollar, despite the building recovery in Europe. Since the United States is on a solid recovery path and one presently characterized by few imbalances, a strong dollar is overall positive for global demand in the short-term, as it improves competitiveness in the rest of the world. Rising oil prices (if they last) from their very low levels are probably net positive for global demand – which is normally not the case – because they ease the adjustment of badly hit oil exporters and of the energy sector across the world. After many years of slow growth and low investment, the world economy is characterized by significant pent-up demand for durable goods, from capital equipment, to cars and household appliances to housing. Corporate and residential investment are rising faster than GDP from low and long-depressed levels. OECD inflation is edging up closer to the 2% benchmark, calming anxiety about the onset of deflation, which would have deleterious effects on borrowers, and especially on the highly indebted public sector.

Consolidation of growth in the US, EU and China is exercising considerable pull on smaller economies, especially on those that are most credit constrained. The gradual emergence of Brazil and Russia from their deep recessions also helps. Higher commodity prices, after 3 years of weakness, greatly help commodity exporters in Africa and Latin America. Non-oil commodity prices are up some 20% on a year ago, whereas the food prices are up only 5%, which is good news for the most vulnerable segments of the population. Private capital flows to developing countries have accelerated, even as large capital outflow from China continues.

In 2017 a ranking of growth of the largest economies, as projected, sees India and China at the top – with growth of 6.5% to 7%, the United States at 2%-2.5%, the Eurozone and the UK in the 1.5%-2% range, and Japan at near 1%. Among developing regions, Asia – excluding China - is likely to show growth in the 6-6.5% range, while the European periphery (Eastern Europe excluding Russia) will show growth in the 3-3.5% range. The weakest aggregate GDP growth – implying stagnant or declining income per capita – is expected in Sub-Saharan Africa (2-3% range), Middle East and North Africa (2-2.5%) and Latin America (around 1%).

Two Medium-Term Scenarios

Though, as already argued, the sustainable rate of global economic growth is quite a bit lower than the 3% of the past quarter century, it is possible that over the next 2 or 3 years the global economy could achieve and surpass that level. There is unused capacity in large parts of the world economy – witness, for example, the high rate of unemployment in Europe and the decline in labor force participation in the United State – and there is vast unexploited potential to improve productivity across the developing world as part of a more rapid process of catch-up with advanced countries. There are very few signs of “overheating”, exception made for localized housing market booms in some cities (e.g. Toronto and Vancouver), or of core inflation rising above targets, except in isolated cases where governments have had to resort the monetary financing of outsized fiscal deficits (e.g. Egypt and Venezuela). Under a virtuous cycle scenario, growth in the United States, the European Union and China becomes mutually reinforcing, leads to a sizable acceleration of world trade, higher commodity prices and higher rates of investment with increased capital flows directed at emerging markets. Under this positive scenario, growth accelerates in the hardest rich regions, including most countries in Africa, Latin America and Central Asia. A combination of higher oil prices and recovery in Southern Europe helps boost prospects for the Middle East and North Africa.

A darker scenario is also possible, however, and perhaps more likely. Driving this outcome would be profoundly inconsistent policies in the United States, consisting of a desire to cut taxes, and increase infrastructure and defense spending while insisting on lower bilateral trade deficits with the nation’s main trading partners. If pursued to their logical conclusion, these policies are bound to result in a marked increase in protectionism and more broadly in international frictions (“trade war”), and, quite possibly, a sharp acceleration of inflation – all of which would profoundly affect investor confidence in the United States and across the world. In a bid to sustain growth, these developments could trigger (or be accompanied by) even more credit creation and fiscal stimulus in China, where large parts of the corporate sector has become highly leveraged. Populist and nationalist parties would gain even more credence in Europe and elsewhere. It is possible to imagine these developments unfolding into a global crisis, leading to a sharp slowdown in global economic growth if not an outright global recession.

The outlook for the MENA region, and more specifically for Morocco must be evaluated not only against the current favorable conjuncture in 2017, but also against the profound uncertainties that loom further ahead.

Implications for Morocco

Although Morocco has been able to uncouple from its surrounding region to a degree, the instability which continues across the Middle East North Africa has important bearing, and reinforces the need to build buffers and adopt policies that are robust in the face of uncertainty. The MENA region is today a theatre of five civil wars (Libya, Sudan, Yemen, Syria and Iraq), large flows of refugees, and profound domestic divisions – such as over the prevalence of a secular or religious state – which will not be easily or quickly settled. Meanwhile low oil prices – which help Morocco – require major adjustment in Algeria and in several countries across the region. Lack of clarity over the policies that will be pursued by the new US Administration and the European Union’s preoccupation with Brexit and its own direction add to the complexity. The outlook for the MENA region in coming years is unfortunately one of low growth combined with high uncertainty.

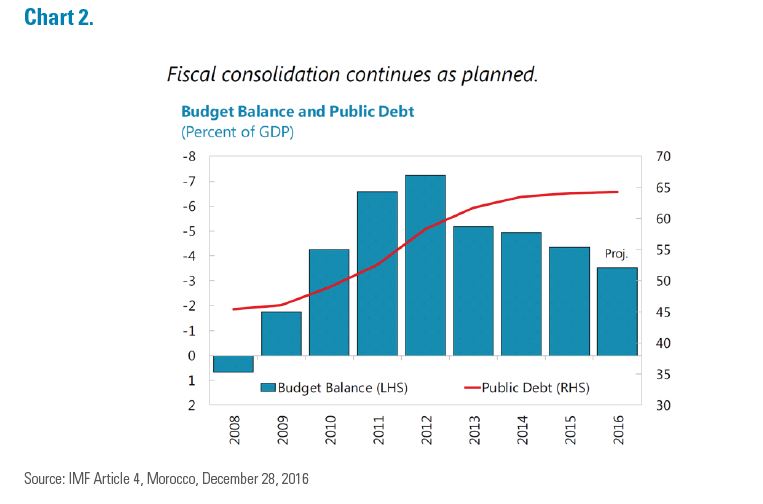

The Moroccan economy, even against this background, is on a solid recovery path is 2017, on its way to growth near 4%, as it rebounds from the weather-induced production decline of cereals in 2016, and despite the continued pursuit of necessary fiscal consolidation Chart).

Foreign currency earnings are being sustained by coming on stream of new export sectors (automobile and aerospace) – despite their requirements for imported materials and parts – and by the gradual recovery in Southern Europe. Earnings from tourism are holding up, as are the inflows of remittances and foreign direct investment. Morocco exports little to the United States, so will not be affected directly by eventual protectionist action, nor does Morocco rely on inflows of portfolio investment and so will not be directly affected by the rise in US interest rates. The exchange rate exposure on Morocco’s public debt is also limited. Low oil prices help, and Morocco has used the windfall well, employing it to lower its current account deficit and improve its fiscal accounts by reducing energy subsidies. (Chart on Public Debt). Morocco has also seen significant progress in its investment climate, as measured by the World Bank’s Doing Business indicators, and is now more highly ranked than would be projected based on its per capita income level.

However, Morocco continues to exhibit important structural weaknesses, which make it especially vulnerable to adverse regional and global scenarios as described above. These weaknesses have been most clearly illustrated by a recent study by Taoufik Abbad (reference), who identifies low labor productivity growth and low income per capita growth despite a large share of national resources devoted to investment. According to Abbad, Morocco’s disappointing long-term growth outcomes can be ascribed to a low quality of investment, in sectors and activities where the rate of return is low, inadequate workforce skills, the prevalence of barriers to movement of factors to higher value added sectors, including rigidities in the labor market and insufficient competition in product markets.

To become more resilient, Morocco needs to continue its path of fiscal consolidation, especially by ensuring that wasteful subsidies are reduced and that public investment is more efficient. As has been often said no reform is more important than improving outcomes in public education, which does not necessarily mean spending more, but making sure that the money is used well and waste is reduced. Both labor and product markets need to be made more contestable and less driven or dominated by connections. The balance of payments can be made more resilient by introducing greater exchange flexibility, orienting more trade towards Asia, the Americas and Africa and less towards Europe, and diversifying the domestic economy and exports not only towards manufacturing but also higher value added services. Continued efforts to improve the business climate and spur competition should also be instrumental to attracting increased foreign direct investment, especially in activities that help integrate Morocco in global value chains.