Investing in “Migrant” Human Capital

With the arrival of more than a million refugees in Europe, the majority of them Syrians, the migration crisis of 2015 left a profound scar on the continent. Not only were borders overwhelmed by migrant flows beyond the management capacities of the European countries concerned, but severe divergences among EU members were exposed and difficulties arose in reaching consensus on an agreed procedure and approach to contain migrant flows. More seriously, the crisis triggered the popularization of populist rhetoric across the continent making migration the argument of choice for isolationism, a phenomenon seen most strikingly through Brexit.

Where then does the crisis lie? Is it in the million refugees whose registrations, dissemination and file processing needed to be managed then, as they still do today? Or is it in the search for a common policy to address the consequences of the 2015 crisis and prepare for potential future crises? In other words, is it a political crisis in Europe or is it an immigration crisis towards Europe?1 Migratory trends illustrate that 2015 events were exceptional and that migrant flows tend to revert to their normal rhythms2. These rhythms have been managed for years without significant difficulty. The current crisis seems more political, between European countries, than migratory. Nevertheless, forward-thinking Europeans are looking for sustainable solutions to similar crises.

1. Hot Spots, Not Exactly the Best Answer

In the wake of exceptional migrant flows in 2015 and the ensuing political turmoil, Europe now seeks effective and sustainable mechanisms to permanently and structurally address such crises, particularly concerning migration from Africa, considered structural, unlike the Syrian and Afghan waves, seen as a mere situational "scourges." While structural measures to deal with a structural phenomenon represents a logical sequence, is the design of exceptional measures to deal with African migration, in its current proportions, justified? African migration is far from reaching the magnitude of the 2015 migrant flows, is relatively controllable, and has not generated acute crises. Should it then be treated the same way? Logic dictates that exceptional measures should be reserved for events of the same nature.

It was following both the event and the ensuing grey and undetermined crisis of 2015 that the idea of outsourcing hotspots, which had hitherto been installed in countries on Europe's external border, arose.

What does the concept consist of? Establishing centers in African countries, particularly in the Maghreb, to sort out those eligible for asylum among European immigration candidates. The concept raises a number of both policy and technical questions:

• Who will direct candidates to these centers?

• Who will question them and process their files?

• Who is in charge of dealing with those who have not been admitted?

• Will they be redirected to countries of origin or entrusted (left to their own devices) to hotspot host countries?

Leaving aside technical aspects, which can always be resolved by professionals, the political side of the issue persists. The establishment of European facilities on African lands can only be interpreted, if not by leaders, then at least by populations, as infringement on the sovereignty of countries hosting future hot spots. In an attempt to appease the crowd, some equate these hot spots with European consular offices in Africa, which issue visas.

Similar screening is also carried out in these offices to assess the eligibility of applicants and their admissibility to the territory of visa issuing countries. There is however, a large-enough both legal and functional nuance for it not to be ignored. As such:

• No diplomatic or consular legation stores inside its walls except for a brief interview period and the completing of forms.

• Visa application is a voluntary process on part of the candidate, while the migrant client of a hot spot will be led to it by force, if necessary.

• A visa applicant is free to move if his application is refused, while a candidate processed in a hot spot will be returned to his country manu militari, unless the country of the hot spot is his country of origin.

The question of sovereignty, combined with technical considerations, leads to insurmountable difficulties. Several countries, anticipating reactions from their populations, have announced their refusal to host such centers before even being officially contacted.

2. Asking the Right Questions

Answering the first question that needs to be asked, is a decisive step in understanding the problem. This first question is the following: What is the composition of the migrant flow that is now breaking into Europe from Africa? Are they refugees? Are they immigrants looking for work? In no event should the answer be based on 2015 statistics. This influx was exceptional in that year. It may have not been spontaneous and those who would have caused it would have had their own objectives. Finally, this influx was not African and can therefore not serve as a reference for a reflection on African migration.

Candidates for illegal migration, transported by mafia migration networks to transit countries and then to European coasts, are largely job seekers. To elaborate, migrants are composed of people of varying ages who aspire to improve their lives and who undertake a clandestine crossing of the Mediterranean at the risk of their lives.

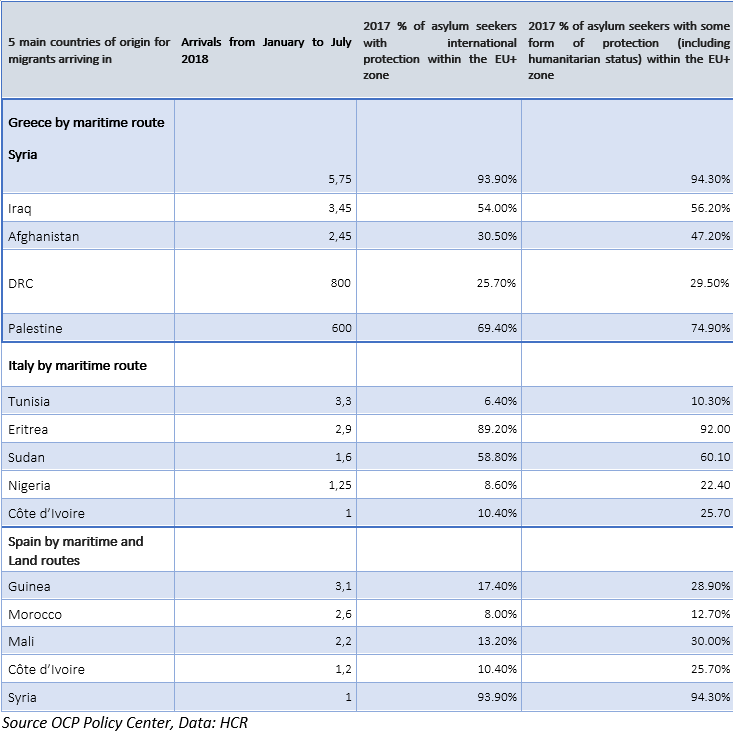

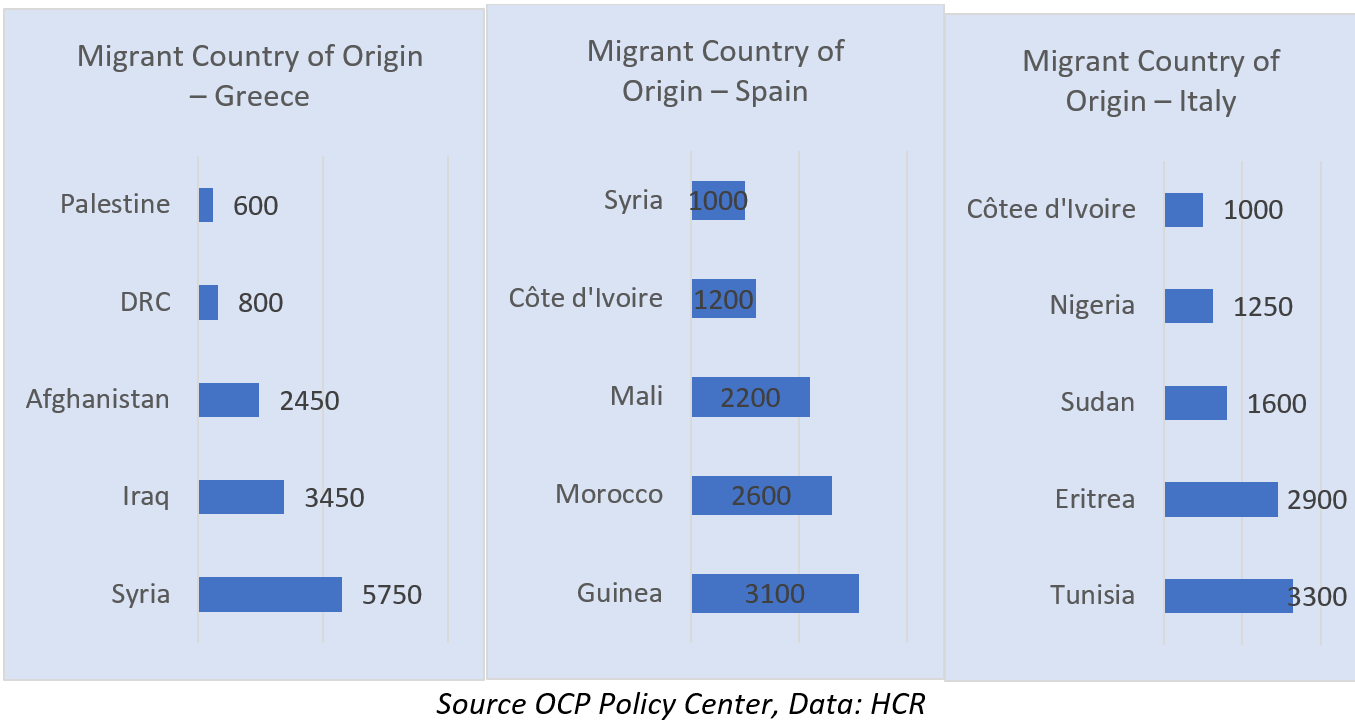

The graph below shows the granting of international protection in 2017 by migration route. Asylum agreement rates for migrants transiting through Spain and Italy (mainly African) are significantly lower than those of migrants transiting through Greece, mainly of Syrian and Iraqi origin. This indicates that many applicants are not fleeing wars or conflicts and accordingly their asylum request files are, albeit in case of error, rejected. EU countries would not reject such a number of files if applicants were genuine refugees.

The demographic profile of African migrants is even more instructive in terms of identifying the nature of migrants, as it shows that African migration is largely composed of job seekers and not asylum seekers, and is characterized by the dominance of men (a demographic category generally known to be more active in the labor market). Indeed, women and children make up 60% of migrants transiting through Greece, unlike Spain and Italy where they represent only 25% and 29% respectively.

The issue is therefore more that of immigrants seeking employment than that of people fearing for their lives and fleeing conflict.

This hypothesis is supported by refugee settlement maps. Africa receives most of African refugees, just as the Middle East receives genuine Middle Eastern refugees. People fleeing wars in Africa settle in the nearest place where they feel the minimum required security is present. The map below shows that asylum seekers, real ones, are settled near areas of tension. Asia (Middle East) and Africa, where conflict zones are located, are home to the Top Ten countries hosting refugee reception facilities.

By asking the right question, that of knowing who the migrants arriving in Europe through Italy and Spain are, one finds that they are much more frequently economic migrants than asylum seekers fleeing conflict.

The challenge, therefore, is to regulate this economic immigration via structural solutions and in a preventive way. Thus, the questions that should be addressed are:

1. How to protect oneself against the anarchy created by human trafficking networks and illegal migration.

2. How to organize and render regular and regulated a mobility, today characterized by clandestineness and disorder.

Demographics, climate change and resource scarcity are all factors that are likely to make economic migration from Africa to Europe a source of risk in years ahead. It is necessary to reflect on the subject in order to avoid the hazards of uncontrolled outcomes on this issue. How then can we channel this migration to better control it? Or, how can we deal with people applying for migration to determine their admissibility without violating their dignity and that of their respective countries?

3. European Immigration Qualification Centers

The idea of setting up European immigration training and qualification centers in certain African countries should replace that of hotspots. By its nature and name, the new concept would be more in a spirit of cooperation and partnership than in a spirit of foreign interference and intervention on African soil. Thus, the question must be posed: How can states implement convincing migration control results while avoiding direct interventions, considered in Africa as infringing on sovereignty and reminiscent of less glorious periods in the history of Africa/ Europe relations ?

Political and technical details of such an initiative can be refined by specialists, however some of its contours can already be identified (e.g. eligibility criteria for African countries to host such centers, and key stakeholders involved).

- Context and General Considerations

If one accepts that African migration to Europe is predominantly economic, it is only logical to apply a solution of the same nature to it. In this respect, an approach is a prerequisite to any conception of a solution. This approach is a first step in depoliticizing migration by cleansing it from residues of decades of security policies, inspired by linear logic (donor-receiver). The consideration of sustainable formats for mobility is the responsibility of all countries issuing or receiving immigrants. Thus, African countries should not only be involved in enforcement phases of migration, but they should, more importantly, be involved from the very beginning of the process. This is particularly important in the case of the project for European immigration qualification centers. All stakeholders (States concerned, migrants, ministries, private actors, NGOs) must take ownership of the project. Political commitment is clearly a prerequisite for the success of this strategy.

As with any project, a feasibility study must be carried out by a specialized firm. In this contribution, we will limit ourselves to 5 basic questions that will allow us to delineate the perimeters of this initiative.

I. Which countries would host these training centers?

The project can start with a sample of countries, for which some key criteria will be selected:

• Above all, political will. For this project to succeed, governments of requesting countries need be involved from the earliest stages of the design. These will preferably be countries that have already shown an advanced level of cooperation with European counterparts on similar issues.

• Next, the availability of appropriate infrastructures and human resources capable of receiving and training migrants is to be examined. One possibility is to start with Maghreb countries, most of which have developed partnerships with the EU3 and some of which, such as Morocco, already have a well-defined migration policy4. These countries being countries of transit, they can also host nationals from other African countries in their qualification centers.

II. For which jobs should migrants be trained?

The answer to this question depends on two factors:

1. The first is the result of identifying sectors of underemployment in Europe. Each European country wishing to receive migrants would make the sectors of its economy where labor needs are felt known. This would involve an analysis of sectors in need of manpower and minimum qualifications required for such jobs. Requirements would also determine languages to be learned by candidates according to country sought. For instance, if a given country needs skilled electricians and mechanics, the contingent for that country would be trained in those sectors, would learn the language of that country and would also be provided with elements to facilitate his/her integration.

2. A second factor depends on the candidates themselves. On arrival at the center, after interviewing with professional counsellors, applicants would provide their language qualifications, diplomas (if any) and training preferences. Ideally, training in sectors with high labor needs should be prioritized, as this would improve chances of integration of trained migrants, either in Europe or in countries where they are on training.

A qualified workforce is always in demand, regardless of its geographical origin. Strengthening modules in oral communication and other inclusive skills would be an asset in all training.

III. How to assess and recognize qualifications acquired during training?

The formal recognition of qualifications acquired during training has at least two benefits. First, to serve as an incentive for migrants to engage in training leading to a qualifying diploma, which can always be used for employment. Then, to help project managers evaluate everyone's performance in a transparent way. Better ranked candidates can thus access job opportunities more quickly. Methodologies used in informal education or continuing training can serve as models for developing such a curriculum. A candidate's performance on the training and scores obtained at the end of the training period may also determine the duration and nature of contracts he or she can obtain.

IV. How to ensure the professional integration of migrants?

This particular issue encompasses the full complexity of the project. Support from non-state actors is essential for success of the project. In fact, the support of numerous private actors and NGOs in European and African countries is necessary. It is also necessary to ensure a base of reliable partners who can engage in such an initiative. Everything depends on the project's narrative. NGOs and/or the private sector can be key potential employers of these migrants. In addition, judicial mechanisms will need to be provided to facilitate the integration of workers from these training centers by potential employers. More interesting still, such initiatives may be treated as corporate social responsibility and tax incentives and facilities may be offered to companies that wish to participate in the program.

V. What difficulties are associated with the initiative?

Future outcomes in projects involving the human element are often difficult to accurately anticipate. In this project, the psychological element has a major role to play. How would it be possible to ensure that migrants themselves buy into such a project? How can these training centers convince a migrant who has travelled a long and dangerous journey to Europe to end up in another African country, and to wait two or three years before arriving on the northern shore of the Mediterranean? These complex questions require well-thought-out answers. The foundations are trust and the delivery on promises. If migrants are to be promised legal access to the European labor market, this should in fact be done.

Conclusion:

There has been general awareness in recent years of the importance of changing perceptions on migration, but all attempts to change the narrative come up against a wall of anxiety and security concerns. The European Commission in 2011 spoke of the importance of addressing root causes of migration, i.e. lack of employment opportunities, underdevelopment and political crises. Well prior to that, the same institution once endorse a prosperous Euro-Mediterranean neighborhood where mobility is encouraged. In practice, however, it is increasingly difficult for nationals of the South to access the North. Extremely long and complex visa policies, combined with prejudice and the frightening rise of right-wing parties in Europe, deepen the gap between two areas that are nonetheless very close to each other.

Through an ambitious proposal from Morocco, the African Union decided in 2018 to adopt an African vision of migration. It is a real opportunity to be seized, especially since the next international migration meeting under the aegis of the UN will be held in an African country, Morocco. The UN Global Pact now addresses safe, orderly, and regular migration. Investing in the development of migrants through vocational training is no doubt a first step towards such mobility. This was used, in a recent past, by both source and host countries to meet part of their economic needs, according to the simple law of supply and demand. While the economic context has changed, the benefits of organized human capital mobility are undeniable. Demographic, social and economic trends are such that part of the South's needs is in the North and vice versa. As a result, to take full advantage of the demographic diversity of the two areas, it is essential to see mobility differently. It can no longer be thought of as disconnected from the economic realities that shape it.

***

1 - At a meeting with 16 of his European peers in June 2018 in Brussels, President Macron said: ''The challenge we face is one related to political pressure in some Member States.... Some are trying to exploit the situation in Europe to create political tension and manipulate fears.”

2 - See: https://www.lemonde.fr/europe/article/2018/06/28/migrations-vers-l-europ...

3 - These include cooperation within the European Neighbourhood Policy and bilateral action plans.

4 - Morocco has had a National Immigration and Asylum Strategy (Stratégie Nationale d’Immigration et d’Asile) since 2014. It has also naturalized a large number of migrants residing on its territory.