State, Borders and Territory in the Sahel: The Case of the G5 Sahel

This Policy Brief highlights the depths of the Sahel crisis. Some aspects of the crisis, such as extremist violence, migration, transnational crime and precariousness, are in fact symptoms of a disease that will only get worse if the real and deep causes are not addressed. Exploring the case of the G5 Sahel as a framework for the convenience of study and analysis does not imply that the crisis is limited to the five countries that are part of the G5 Sahel. Indeed, while specificities must be taken into account, we must recognize certain difficulties, particularly structural ones, that remain common to all the countries of the region.

Increasingly frequent attacks in the Sahel, in spite of United Nations peacekeeping missions, the French Barkhane operation and the military presence of various countries in the region, raise a number of questions:

• Are terrorist movements in the region so powerful and so capable of resistance that all the initiatives undertaken to counter them, taken together, remain ineffective to ensure peace and security in this region of the world? The region's observers and experts concur that the region's terrorist groups are composed of just a few hundred, perhaps even a few dozen fighters. Even their federation called " Ansar Al Islam Wa AL Muslimoun", formed last March, did not increase their numbers. It only coordinates operations and shares areas of action.

• Are the measures taken so far inadequate or inappropriate for this particular situation? Some argue that significant resources are poured into a war effort that does not match the true needs of the population. Their livelihood is under higher threat than their physical security.

• Are the measures pursuing inappropriate goals, treating symptoms rather than the disease? Several analysts contend that terrorism, organized crime and other scourges are but the consequences of more serious ills, which form the root of the problem and which must be addressed in order to remedy the situation.

Such is the context of this analysis of the Sahel. Precariousness, poor governance, or the spread of jihadist ideologies have often been cited as reasons for the phenomenon that jeopardizes the stability and development of the Sahel. Isn't it time to look into other data at the source of precariousness, poor governance and therefore the spread of extremist ideologies?

Covering immense territories, controlling tremendously long borders, the relationship between center and periphery, the modest resources compared to the scale of the challenge and the extent to which populations have internalized the concept of a nation-state: these notions may be helpful in analyzing the situation in the Sahel to understand the disease afflicting the region.

Measuring the impact of terrorism on the population, and comparing them to the consequences of other threats, could provide an analysis that would help to better focus efforts.

The population's relationship to the State in countries of the Sahel should also be examined, not just in terms of governance, but especially in terms of how situations are perceived. Do populations have similar perceptions of notions such as security or prosperity? Do they have a similar understanding of the concept of sovereignty, borders, or allies and enemies?

Do States and populations strive for the same goals? If not, do these goals at least not contradict one another?

Don't socio-economic inequalities and wealth redistribution issues in African or Sahelian countries constantly widen the gap between a wealthy ruling elite, and the middle class and the poor who have a hard time finding a way to live with dignity?

In order to frame the analysis, this paper will remain limited to the G5 Sahel countries. On that account, a brief description of the G5 Sahel is needed, before any notions of State, borders, territories and governance are addressed.

I. The G5 Sahel: Nature and objectives;

principles and area covered

The G5 Sahel (G5S) is an initiative born in 2014, established by a convention signed by five heads of State. This initiative can be symbolized as a square, with each angle representing a situation, a goal, an area and an organization. With these four building blocks, a geopolitical analysis lies at the intersection of geography, policy and strategy:

• Some recitals in the preamble to the convention creating the G5S describe the situation in the Sahel;

• Article 4 of Title II sets out the goals, which are essentially to ensure development and security to improve the population's quality of life. Special focus is placed on using democracy and good governance as means to that end, and international and regional cooperation as a framework for such efforts;

• The preliminary title specifies that the G5 Sahel refers to Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso and Chad. The area in question is thus the combination of these countries' territories;

• The organization and its statutory bodies are described in Title III.

Our purpose is to explore whether the G5S organization and the States that constitute it (political tools) are likely to effectively act in a given area and with a given population (geography) to establish peace and prosperity (strategic objective), despite a situation characterized by insufficient resources. This can take the form of a few questions:

• Since the independences of the 1960's, a multitude of organizations, regional and sub-regional entities have proliferated in Africa, sometimes complementing one another and sometimes competing or even opposing one another. Is the G5 Sahel just adding to countless organizations?

• Is the G5 Sahel, an organization bringing together 3 countries from West Africa, one from the Maghreb and one from the ECCAS, an opportunity for cooperation between these three entities, or would it become a bone of contention?

Before answering these two questions, the convention should be briefly examined, in order to find out about the organization's key principles and territorial boundaries. What are the foundations of the G5S and where does it act? This answers some questions about the number of countries involved. Why just these countries and not others? What is the nature of the organization? Is it an attempt at integration, or is it simply a framework to pool resources?

1. Key general concepts behind the G5S philosophy, according to the G5S convention

Several terms describe the philosophy that underpins the G5S: democracy, good governance, security, peace, prosperity, integration, solidarity, etc.

These concepts can be subdivided into two categories: objectives on the one hand, and actions and means on the other:

• Security, development, peace, prosperity are notions contained in the G5S convention which illustrate the organization's ambitions and the goals it intends to meet. The preamble to the G5 Sahel convention declares that signatory States are "determined to combine efforts to make Sahel a region of peace, prosperity and concord". It later adds that its countries are "convinced of the interdependent nature of the challenges of security and development". Paragraphs 6 to 9 of the preamble on the organization's motives all contain the words "security" and "development".

• Democracy, good governance, common action, regional integration and solidarity are repeated often in the convention, as means to reach the G5S' goals. Paragraph 5 of the preamble declares that States are "convinced that only joint action from our countries can meet the challenges ahead" and that "regional integration and solidarity among States are essential prerequisites". Later, in paragraph 7 of the preamble, States reiterate that they are "fully committed to promote democracy, human rights and good governance".

However, it must be noted that the convention raises the issue of sovereignty, which without being clearly mentioned, emerges from the comparison between the general principle of regional integration, announced in the preamble, and the true nature of the organization defined in the first article of Title I: "an institutional framework for coordination and monitoring cooperation". Is regional integration merely an institutional framework for monitoring cooperation?

2. The area covered by the G5S convention

The convention also raises questions about the geographical boundaries. The terms "Sahel", without further clarification, and "G5S States" are used without distinction:

• The preamble alludes to the Sahel in its general sense. In the first eight paragraphs, the convention mentions the Sahel without delimiting any specific area:

• In paragraph 2, the preamble sets out the objective of "making Sahel a region of peace, prosperity and concord".

• When listing challenges, the convention does not refer to the countries involved but to the Sahel in general.

• Paragraph 6 also mentions the Sahel in general and paragraph 8 the Sahelian region. The phrase "G5 Sahel States" appears for the first time only in the 9th and last paragraph of the preamble.

• The use of the two terms "Sahel" and G5 Sahel States" can be interpreted in different ways:

• The first interpretation is that the authors of the convention consider that the Sahel region is limited to the combined territories of the five signatory countries. This allows the convention to use both phrases indistinctly.

• In the second interpretation, the G5 Sahel is only a part of the Sahel, but its action could ensure the security and development of all of Sahel. But in this case, it would have been wiser to specify that the G5 Sahel contributes to the Sahel's security and development, but cannot guarantee it alone.

• The third would be that the authors of the convention consider that the G5 Sahel is a Sahelian institution founded by five countries but which remains open to other countries of the Sahel?

• After the preamble, the phrase "G5 Sahel" is finally defined and demarcated in the preliminary title as a "Group of five countries of the Sahel, namely Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger". Thus these five countries are not "the Sahel", but "of the Sahel". The fact that these countries are enumerated implies a wish to set them apart from the Sahel as a whole. Therefore, the text referred to the Sahel as a whole to describe the situation under consideration, and limited the scope of the G5 Sahel to the five countries listed.

II. The State: a divergence of views between the ruling

elite and the population

The concept of State in Africa has sparked the interest of a large number of political specialists, historians, geopolitical experts, constitutional law experts and anthropologists. The notion of State has been studied from every angle. Some tried to date the birth of the State in Africa, placing it either before or after colonization; others analyzed it from the perspective of legitimacy and prerogatives, while others still preferred to dissect its nature and components (social groups, ethnic tendencies, alliances between clans).

The State in the Sahel is no exception. In the Sahel as in the rest of Africa, several authors, researchers and analysts have wondered whether the Westphalian form of the State, imported by colonialism and established through it in systems of political organization in the Sahel and in Africa, was internalized by both ruling elites and populations - or if populations and ruling elites perceive the State differently. Broadly speaking, the question is whether the transplant was successful, and if not, what the causes or complications have been.

For many specialists, the Westphalian concept born in Europe in response to European situations, cannot claim to be a universal form of the state or of world order. "The seventeenth-century negotiators who crafted the Peace of Westphalia did not think they were laying the foundation for a globally applicable system", wrote Henry Kissinger.

Before colonization, in the Sahel, there had never been a sovereign nation-state such as it evolved in Europe into its current form, the origins of which can be traced back to the Westphalia treaties (1648). In these treaties, monarchs of the time had sovereignty over a given territory and population. The State formalized a feeling of collective identity, initially personified by the sovereign but later embodied in the nation itself after the French revolution. This feeling then becomes one of national identity connected to a territory.

Is this also the case in Africa in general, and in the Sahel countries in particular?

As in all ancient kingdoms and empires, one of the major characteristics of Sahelian empires was that, the further away from the center (capital and surroundings) and the closer to the periphery and fringes, the more diluted the sovereign's power. His control over the outer parts of the kingdom or empire depended on the degree of loyalty of his vassals. Borders were not fixed, well-defined and stable demarcations; the empire's populations were difficult to identify as one moved away from its center. Two kingdoms or empires did not touch; only their peripheries were in contact. The map below shows that empires overlapped both in space and time. This produced areas and populations that were acephalous, or lacking a dominant power, and where the notion of territorial boundaries or national identity were absent.

Source : L’Atlas des Empires : Le Monde N° spécial (2016)

The people of these empires and kingdoms (chiefdoms, tribes or ethnic groups) recognized the power of kings and emperors more out of submission than out of loyalty or conviction. An ethnic group, a tribe, or a dominant religion took power by submitting others until a stronger entity appeared. This was also true of eighteenth and nineteenth century Muslim kingdoms and empires. They were built through jihad and war and therefore by submission by force. Loss of power or sharing power was perceived as a weakness and a defeat establishing inferiority. Taking power was a sign of strength and victory, demonstrating superiority in war.

Under these African empires and kingdoms, the dominated tribe or ethnic group recognized the authority of the victorious sovereign, but did not identify with his ethnic group or tribe. Identity did not stem from the kingdom or empire, which were not nation-states.

On the vestiges of these kingdoms and empires and largely on the basis of the borders of colonized areas, colonial powers decided to create states meant to be "nation-states". This is the foundation of the continent's current political frontiers.

The principle of inviolability of borders adopted in Africa put an end to state claims regarding their borders and legitimized the frontiers established by colonial powers, thus generating some stability. However, one must wonder whether the half-century since the independence of many African countries was enough for Sahelian populations to internalize the Westphalian concept of nation-state. On this point, there is a significant difference between the ruling elites in some countries in the Sahel - and Africa - and large portions of the population. The extent of this gap varies from case to case, as do its consequences. A good example is Mali, where ever since independence, populations in the North do not recognize themselves in the Malian nation-state. This is also the case in Niger, though to a lesser extent. In Mauritania, problems of democracy and governance, encapsulated in the gap between black and white populations, ultimately have to do with the unease of black non-Arab citizens who do not identify with a nation-state that defines itself as Arab and where whites have monopoly on power.

The fringes of the population who do not identify with the Nation-state are generally marginalized or oppressed groups who question the legitimacy of the State that they are asked to identify with. These populations, going beyond the forms of legitimacy identified by Max Weber, deem that their state lacks functional legitimacy, and therefore that the ruling authorities are not valuable.

Using the criterion of legitimacy as a starting point, populations feel no need to consider as legitimate and deserving obedience a state that does not fulfill its duties to those who are supposed to be its citizens. The state is concentrated in the capital where development actions are focused; when it comes to the periphery, the outer limits and the marginal populations, the state provides only citizenship and administrative identity documents. Some countries of the Sahel lack the resources and in some instances the political will (partly as a result of history) to control the entirety of their territories or to systematically protect all their borders, much less to manage all populations. Thus what differentiates them from ancient kingdoms, empires or chiefdoms is simply their electoral systems (however reliable), their constitutions (however adequately enforced), the administrative organization of capitals and the discourse on the modern nation-state adopted by ruling elites.

For populations in the periphery, governance hasn't fundamentally changed since pre-colonial times. The actions of an ancient king or emperor and those of a modern president become increasingly diluted as one moves away from the capital, and the benefits of power grow smaller as one moves away from one's family, clan, tribe or ethnic group.

This chasm between the ruling elites' and the peripheral populations' conception of the state is a factor of destabilization in the Sahel, which finds separatist, terrorist and criminal expressions.

Sahelian states can only guarantee long-term stability by exercising their authority on all their territory, by restoring functional legitimacy in the eyes of all their citizens, initially by putting forth a fair and balanced development effort and true and sincere decentralization, which ensures unity while avoiding uniformity and allows for close and tailored governance.

III. Territory and population: an inequality that

generates grey zones

The area covered by the G5 Sahel adds up to a total of 5,090,725 km2. Four of them cover over one million km2 (see Table 1). Most of this territory, between the Sahel and the Sahara, is desertic, with very harsh living conditions.

Four out of the five Sahel countries have a largely desert climate. The Sahara and the Sahelian steppe cover 50 to 70% of their surface area, excluding Burkina Faso:

• Burkina Faso is the country with the least desert compared to the other four; half of its area is subject to land degradation, in particular desertification. The north and far north of Burkina Faso are past the point of no return.

• Chad is a vast landlocked country. In its strict definition, the desert covers 50% of the territory, and up to 80% if the "Sahelian savanna" is included in the definition.

• Northern Mali, which represents two thirds of the country's surface area, is entirely desertic.

• Mauritania is essentially desertic, with the exception of the southern part of the Senegal river floodplain, of which two thirds are situated in the Sahara.

• In Niger, the North, which constitutes two thirds of the territory, is located in the Sahara.

This desertic aspect impacts population settlement. The average density is 15.5 people per square kilometer (Africa's is 32 people/km2). In terms of regional population density, the G5 Sahel's is among the lowest. Three countries have similar figures for this metric (Mali, Niger and Chad). They are surrounded by two extremes: Mauritania, with 4.1 people/km2, and Burkina Faso, with 70.5 people/km2 (see Table 1).

The low density combined with climate hazards and the desertic, arid climate lead to a population that is concentrated in some areas of the country, while a minority is scattered in areas with a hostile environment. These are largely border areas.

Such a configuration of population and territory generates internal geopolitical dysfunctions. It makes controlling the territory and the borders challenging, if not impossible:

• Climate conditions and the countries' relief make it difficult for any population to settle comfortably and lastingly. Thus, the state cannot lastingly administer the population in these areas, turning them into fringes where the authority of the state becomes increasingly blurry as one moves away from the center.

• Border surveillance, for which exercising sovereignty requires mobilizing such large numbers of military personnel and police that even if they were to be available, the logistics needed to make them operational would be an issue for almost destitute states.

Thus, given its limited resources, the state chooses to be effectively present only where its population is concentrated. Areas with low population density are neglected and only appear in public policy agendas for their sovereignty and security dimensions. The only significance of these areas is military. As a result, in these environmentally hostile regions, there are only poor, nomadic people who seek to survive through trans-border mobility and porous borders. They are left to their own devices. Such areas become grey areas for the following reasons:

• Firstly, these poor and neglected people lose any sense of the usefulness of the state in their daily lives. Therefore, they fall back on traditional and tribal hierarchies and disengage from the state system, sometimes going as far as to demand independence.

• Secondly, the absence of state authorities encourages a lack of enforcement of its laws. Populations who live in grey zones internalize a sense of impunity that enables abuses and the development of illegal activities. Such activities develop not just in the absence of law enforcement, but also as a means of survival in the absence of alternatives.

The immensity of the area that the state has to cover only adds to the political, economic and social instability generated by diverging perceptions of the state among ruling elites and the population. Security and instability threats are only amplified by the disproportional relation between the dimensions of the territory and the means to control it.

This situation requires of the countries of the Sahel to find a way to gradually settle populations by establishing infrastructure that is appropriate for the environment and lifestyle of people who live in the areas that have until now been deemed unworthy of the effort. If this proves to be impossible, the state should innovate in order to both administer populations and provide the necessary public services, using administrative facilities able to deal with population mobility.

IV. Borders: sovereignty should be partly renounced

1. Options for the G5S borders

The G5S borders raise the issue of the degree of cooperation. Either a distinction is made between the external and internal borders of the G5S, which implies common action and territories, or the usual conception of borders is maintained, where only internal borders matter, which involves joint action and separate territories.

• In the first option, each country's border with neighbors that are not in the G5S is considered as an external border of the Group's territory. As a result, the country has responsibilities in terms of security and defense in the entire G5S area.

• In the second option, each country's responsibility is limited to the security and defense of their own territory.

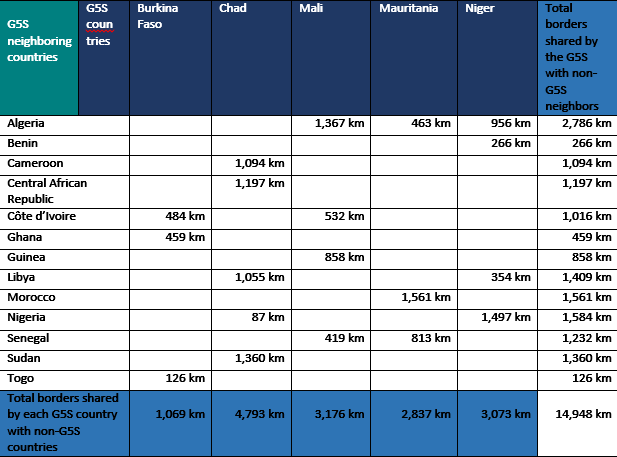

Considering the first option, the G5S would have about 15,000 km of land borders with neighboring countries (see table below). Each country must take measures on the sections relevant to them. The scale of each mission will depend on each country's neighboring environment and the length of the borders shared with non-G5S countries.

With the second option, the notion of internal and external borders disappears. The frontiers to be kept under surveillance become longer, due to the fact that they also include those shared with G5S allies.

As an example, in the first option Mali would have to keep watch over 3,176 km; in the second, the borders with Mauritania, Niger and Burkina Faso add another 4,058 km. As long as each G5 Sahel country does not trust the others to mobilize sufficient resources to keep the external border under surveillance, the length of borders to be defended will remain greater, and more resources will therefore be needed.

Internal borders should not hinder the fight against terrorism and organized crime. These 5 countries should therefore create a single legal area and a guaranteed right to prosecute terrorists and members of a mafia, in a way as to respect sovereignty without hampering law enforcement.

Such an option requires:

• A high level of confidence among countries. Each G5S country should take measures to secure the common area and trust the measures taken by other countries;

• Partly renouncing exaggerated sovereignty, in a way as to consider the whole of the G5S area as common to its people and states;

• Perfect convergence regarding perception of the threat. Each of the five countries must see itself as equally threatened as the most impacted country.

Table N° 2 : Length of borders shared by G5S countries with non-G5S countries

2. How the state and the population perceive borders

In the Sahel, one of the challenges is to find common ground in the perception that states and populations have of borders. These are, at the same time:

• In the eyes of the state, borders are a tool of sovereignty. No matter the relations between populations on both sides of a given border, and regardless of emergency, this political, economic and defense barrier can only be lifted by the state. The state is responsible for opening borders to trade and economic exchanges, and it is its prerogative to close borders and defend them against anything it deems to be harmful to the security and proper functioning of the country.

• In the eyes of the people, the border is a transnational space that they use for informal exchanges and to counteract the insecurity generated by nature and poor governance. When borders divide one same ethnic group or tribe and when the living conditions and the fight against climate hazards require mobility, populations do not bother with a frontier that their collective consciousness has not internalized. Nomads are more concerned about the itinerary that will provide the most food for their cattle than they care about the border or any other type of demarcation. "In Chad, the southern limit of camel herd movements has descended from the 13th parallel to the 9th parallel in 20 years. Some transhumant cattle herds are now being driven as far south as the Central African Republic".

The status of borders should meet two needs: the need for security as conceived by the state, but also the need for fluidity as conceived by the population. The movement of people across the internal G5 Sahel borders to fight for survival in the face of natural hazards predates the movement of terrorists; one should therefore not conflate the transnational movement of people for human livelihood with that of mafia and terrorist groups. This requires resources to control borders and separate the wheat from the chaff, but it is also necessary to adopt the concept of internal borders open to free movement. The G5 Sahel countries should renounce "full sovereignty", otherwise some populations will continue to experience hardship in their lives and will turn to belligerent activities with regard to their state. "In 1998, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) adopted decision A/DEC.5/10/98 to provide a framework and facilitate transborder transhumance, which was locally reinforced by agreements between countries (Mauritania-Senegal-Mali, Niger-Burkina Faso). Fifteen years later, these regulations are still hard to apply in the field and livestock farmers continue to encounter problems when crossing borders".

Conclusion:

The state, borders and territory are key factors in the security/development equation in the Sahel.

The relation between the State and the people, as well as the diverging perception of the notion of state among the people and the ruling elite, amplify opposition between the former who aspire to a functional state and the latter who see in the state a simple apparatus of power which is imposed on populations even if it does not fulfill their needs.

The vastness of territories and their nature (deserts and steppes) leads to settlement disparities that have an impact on the state's presence. The state tends to establish its presence in densely populated areas and to forget the people who live in low-density areas. This situation generates grey areas, conducive to all kinds of trafficking and terrorism.

Borders span thousands of kilometers. This makes their surveillance and protection more challenging. Moreover, just as with the notion of state, the people and the ruling elites have diverging perceptions. While in the eyes of the state, the border is first and foremost about sovereignty, for the population it is a space to meet and exchange and a window of opportunity to protect oneself against natural hazards. Above all, it should permit mobility.

Bearing in mind the role played by territory, borders and the state is absolutely necessary in any initiative aimed at ensuring security and prosperity in the Sahel.

Whether they are national, regional or international, such initiatives should allow states to:

• Be present and available in capitals and in densely populated areas, but also in more challenging and sparsely populated areas where transhumant minorities live, the lifestyle of whom is based on mobility;

• Modify the status of border areas in a way as to retain a minimum level of sovereignty, while also enabling populations to maintain exchanges;

• Design governance modes that prioritize devolution and decentralization while also ensuring that there is solidarity between regions, and foster unity without advocating uniformity.